Dr Fabian Braesemann

Departmental Research Lecturer

Dr Fabian Braesemann is a Departmental Research Lecturer in AI & Work at the OII.

July 2021: As more and more people get vaccinated against Covid, there is hope that the worst of the pandemic is over. Even though the delta variant causes worries of new infection waves, many restrictions are released. As a consequence, on-site working and face-to-face meetings will again become part of our daily routine.

Nonetheless, the pandemic has changed social interactions and the working life for good. Post-Covid, it seems inconceivable that companies will send their employees to the other end of the world for just one meeting – a zoom call suffices. The new habits do not only affect long-distance business flights, they also change daily work patterns. It seems unlikely that companies revert to an ‘old normal’ of mandatory full week office availability on 9-to-5 business days.

Of course, many of us – those who did not enjoy working from home – can’t wait to get their old work life back. If you have to deal with numerous competing tasks at the same time (caring responsibilities, home-schooling and many more) and you lack an appropriate infrastructure to work from home, you count days until you can send kids back to school and return to the office.

Surveys indicate, though, that a large share of the workforce actually finds the home-working experience satisfying. This is because employees can better focus on important tasks, and they consider zoom calls to be more efficient than endless meetings in the conference room. Therefore, it is to be expected that many people will want to continue to work from home, at least some days per week. In that hybrid on-site and remote future of work, employers need to rethink how to coordinate tasks and how to exercise control efficiently.

To do so, some organisations – particularly platform operators in the gig economy [1] – introduced technical solutions, such as the automatic tracking of work time or keystrokes [2], trying to establish control in times of remote work. However, this undermines the trust base needed for the complex jobs in today’s hyper-connected, digitalised economy, which require autonomy, motivation, and trust [3]. Instead of transporting the old time clock to the digital workplace, organisations should seek to foster trust to keep employees motivated and productive in the ‘new normal’ of remote work.

Trust plays an important role in every social and economic transaction. The equation is pretty simple: the more trust, especially trust in strangers and people in general – so-called ‘generalized trust’ – the better the overall socio-economic outcomes of individuals, organisations and societies as a whole [4].

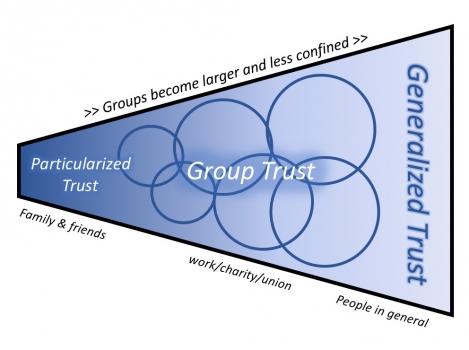

As we show in our recent study Between bonds and bridges: Evidence from a survey on trust in groups [5], generalized trust builds up from other forms of trust. In that framework, ‘group trust’ plays a crucial role (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Different forms of trust are related with each other from particularized trust to close friends and family members, over trust in groups, to generalized trust.

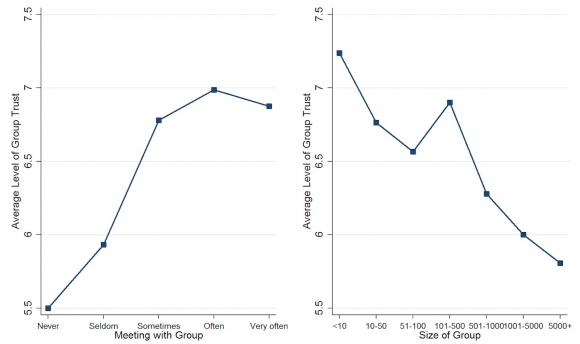

Figure 2 – The trust in groups depends on the intensity of group interactions (left) and the size of the group (right).

The higher the trust in groups, the higher the average level of generalized trust; and hence all the positive individual, economic, and societal effects related to it. Figure 2 shows that trust builds on interaction: the trust a person has in a specific group depends, among other things, on the level of group interactions and the size of the group. That means it is more difficult for people to build trust into large groups – in comparison to small groups – particularly if group members do not interact that often with each other.

Our findings underline the relevance of social interactions in trust building. This is particularly relevant in remote collaborations, as outlined in our paper Coding together – coding alone: the role of trust in collaborative programming [6]: Online programmers are most active in areas with strong social cohesion and trust in others, as summarised in a previous blog post. Without social trust and a sense of belonging to a community, productivity in digital knowledge work fades. These results have an important implication for the post-pandemic organisation of work: The future of work needs trust.

As global teams and remote collaborations make it more difficult to bring people together into one room, it has become harder for organisations to create a team spirit and to foster the ‘person-environment fit’ [7]. Therefore, trust-building digital interactions, autonomy, and proactive HR management are becoming more important – particularly in large organisations where building group trust is difficult, in general. The web is full of great suggestions on how to build the team spirit of the digital workforce, e.g. by virtual break rooms, tours of the remote working location, remote workshops and many more (eg, for example here or here).

If organisations manage to keep a collegial spirit alive that integrates both the on-site and remote workforce, employee-wellbeing and productivity will benefit from the more flexible organisation of work in the future.

References

[1] Wood, A. J., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V., & Hjorth, I. (2019). Good gig, bad gig: Autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy. Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), 56-75.

[2] Leicht-Deobald, U., Busch, T., Schank, C., Weibel, A., Schafheitle, S., Wildhaber, I., & Kasper, G. (2019). The challenges of algorithm-based HR decision-making for personal integrity. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(2), 377-392.

[3] Garton, E., & Mankins, M. C. (2015). Engaging your employees is good, but don’t stop there. Harvard Business Review.

[4] Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251-1288.

[5] Braesemann, F., & Stephany, F. (2021). Between bonds and bridges: Evidence from a survey on trust in groups. Social Indicators Research, 153(1), 111-128.

[6] Stephany, F., Braesemann, F., & Graham, M. (2020). Coding together–coding alone: the role of trust in collaborative programming. Information, Communication & Society, 1-18.

[7] Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183-187.