Professor William H. Dutton

Senior Fellow, Advisory Board Member

Bill Dutton was the OII’s Founding Director, a Fellow of Balliol College and the first Professor of Internet Studies at Oxford University.

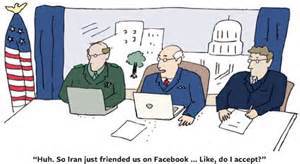

Recent Chinese concerns over ‘Twitter Foreign Policy” are just the tip of the iceberg on the ways in which the Internet has been enabling diplomacy to be reconfigured, for better or worse. Over a decade ago, Richard Grant, a diplomat from New Zealand, addressed these issues in a paper I helped him with at the OII.[1] Drawing from Richard’s paper, there are at least five ways in which the Internet and social media are reconfiguring diplomacy:

These transformations do not diminish the need for diplomats to serve a critical role as intermediaries. If anything, the Internet makes it possible for diplomats to be where they need to be to facilitate face-to-face interpersonal communication, making the geography of diplomacy more, rather than less, important. However, it poses serious challenges for adapting diplomacy to a globally digital village, such as how to adapt hierarchical bureaucracies of diplomacy to respond to more agile networks, and how to best ‘join the conversation’ on social media.

[1] Richard Grant (2004), “The Democratization of Diplomacy: Negotiating with the Internet,” OII Research Report No. 5. Oxford, UK: Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford. See http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1325241 Also discussed in a talk I gave last year on Mexico in the New Internet World, see: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2788392