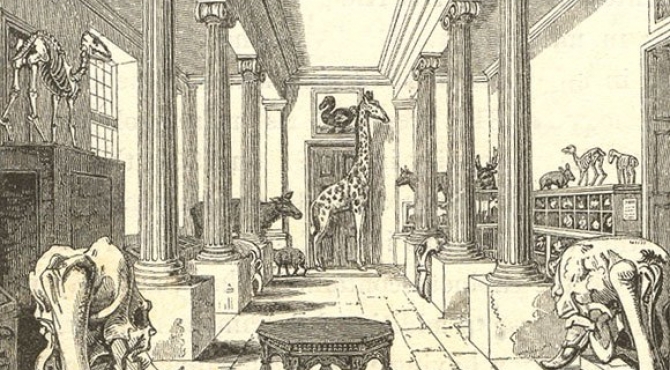

How far back do our modern day practices of collecting, curating and displaying information go? Choosing a Facebook profile picture, creating a gallery of holiday photos, tweeting an image of a strange object you’ve come across – all of these acts have historical roots, taking us right back to the Renaissance period and to the strange and mystical Cabinets of Wonder.

On 15th May 2015, members of the Digital Knowledge and Culture group took part in the Ashmolean‘s LiveFriday event, which opened up the museum and the university to the public for a night of experiments, demonstrations, theatrical performances, creative workshops and exciting talks. Using a custom built Digital Cabinet of Wonders, we asked participants to think about how collections of items from the past can help us to think about our own world. For instance, John Tradescant collected a hawking glove from Henry the VII that lets us think about whether the glove would be as interesting to us were it not for the association with royalty? Are we looking for a similar connection when we follow the Twitter account of Stephen Fry or Justin Bieber? And when we store our relationships and memories on transient online platforms, will our future ability to reconstruct those interactions be just as difficult as trying to work out the habits of the Dodo from a taxidermy specimen?

Let us show you some of the objects in our Digital Cabinet of Wonders, and we will explain why our research into their contemporary counterparts sheds light on what it means to be human in the 21st Century.

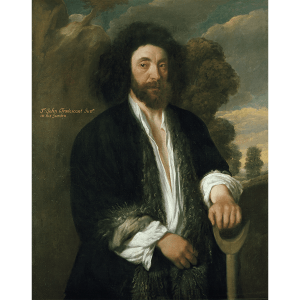

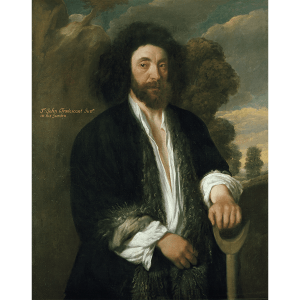

Portraits and profile pictures

Some of the richest and most vivid paintings of wonder cabinets, or kunstkammer, are those by Frans Francken the Younger (1581-1642). In capturing the sumptuous nature of many of these cabinets, Francken also depicted numerous portraits within them, thought to be the owners or collectors. Portraits, which historically depicted the wealthy and influential, were usually intended to flatter the sitter, and their construction intensely careful and controlled.

In our modern digital wonder cabinets, we are in control of our own portraits, or profile pictures, and can change, emphasise or obscure certain features or unflattering poses. Choosing the right profile picture can reveal so much about who we are, what matters to us, and how we choose to reveal this information. People who have used social media sites over a prolonged period of time will have chosen multiple profile pictures, curating a gallery of images or series of performances, through which other users can gather and intuit information.

With the rise of the smartphone, a new connection between the portrait and the profile picture has emerged, with the rise of the #museumselfie. Museum selfies usually feature the visitor capturing the moment they interact with a famous portrait or painting. In this way, the digital wonder cabinet functions not only as a means of displaying a person’s own curated collection, but also their good taste in seeking out other objects of meaning and value.

You can read more about the work that OII Research Fellow Dr Bernie Hogan has done in this area

here.

Travel and Exoticism

Cabinets of wonder were essentially performative, as well as contemplative spaces, where the curator could collect and display objects that created a refined sense of culture, as well an indication of wealth and power. The original cabinets often contained curious and beautiful shells, minerals and other geological samples, as well as ethnographic specimens from distant and exotic locations. They also contained many images and statues depicting the classical world. These objects and images collectively displayed the wonders of the world, and the discernment with which the collector had chosen and assembled them.

Cabinets of wonder were essentially performative, as well as contemplative spaces, where the curator could collect and display objects that created a refined sense of culture, as well an indication of wealth and power. The original cabinets often contained curious and beautiful shells, minerals and other geological samples, as well as ethnographic specimens from distant and exotic locations. They also contained many images and statues depicting the classical world. These objects and images collectively displayed the wonders of the world, and the discernment with which the collector had chosen and assembled them.

Not only has travel become within the financial reach of many more people, the digital wonder cabinet puts the means of display well within reach. Facebook, Flickr, Tumblr and Instagram have created vibrant repositories for images of our travels, and have enabled us to invite our followers and friends to observe and reflect on the meaning of our encounters. Functioning both as theatres to perform aspects of their owners identity, and as repositories for memories of travel. In pasting our holiday photographs into Facebook albums, this dual purpose is also being served, archiving images and memories that are valuable to us, while showing those in our communities and networks how enriched and cultured we have become through our travels in the world. But beware, posting excessive numbers of holiday photos could cause unfriending…

Mystery and Imagination

The original wonder cabinets were truly eclectic, and highly individual collections of items designed to inspire thought and contemplation but also surprise and inspiration. In the collection of John Tradescant, which formed part of the founding collection of the Ashmolean Museum, there were many exhibits from the natural world to inspire and enthuse visitors, such as an ape’s head, a flying squirrel and a salamander. There were also yet more mysterious items, such as a mermaid’s hand. Other wonder cabinets included unicorn bones, and collections of deformities. Such fantastical objects were particular treasures of the wonder cabinets.

This appetite for the carnivalesque is certainly something we can see through the modern day parallels of Facebook and Twitter. Animal mashups, for example, a photography meme curated and presented via Twitter, creates new animals by using software to join them together in a highly convincing way, fostering a sense of wonder and possibility. What if such animals could exist? These are funny but clever and challenging images that force us to consider what is known and unknown, and how the world we live in can continue to surprise and entertain us.

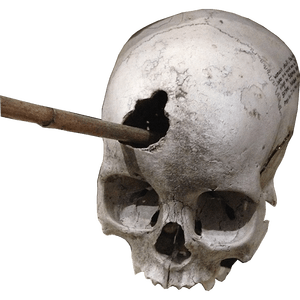

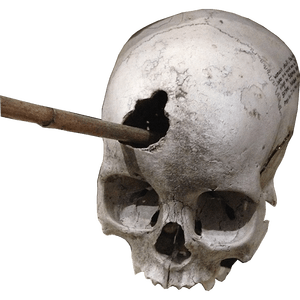

Death

The original cabinets of wonder reveal an ongoing interest in death and mortality, and often featured an object or objects that shed light on different attitudes towards memorialisation. Social media can similarly be used to create and display a communal grief and to memorialise lost lives.

Social media platforms provide a space for collaborative reflection and sense making when the death of a public figure has challenged our sense of a natural order. In 140 characters, a tweet can provide a brief but powerful public declaration of grief, and enable a moment of reflection on our own mortality.

Facebook pages create more intimate wonder cabinets through which to display and discuss such issues, where we reflect on life, death and meaning, for example through posting the anniversary of the death of a loved one. Pages that memorialise and idealise the dead are created as exhibitions such as this one celebrating the late comedian Robin Williams, where grief and loss can be performed as part of a wider collective understanding of their impact on our lives.

Science and knowledge

The original cabinets of wonder were designed to collect and preserve the whole of knowledge. Many cabinets featured objects of significant scientific importance, leading to greater public understanding of scientific practice and discovery. One of the most famous collections was created by 17th century Danish doctor, Ole Worm, containing hundreds of items of natural history carefully arranged in his own home. Upon his death, a detailed catalogue of his cabinet was published as Museum Wormianum, the starting point for his speculations on science, philosophy and natural history, and he frequently used his collection for teaching.

In March 2012, Elise Andrew set up a Facebook group called IFLScience where she curated and commented upon the ‘bizarre facts and cool pictures’ she regularly came across. Just like the original cabinets of wonder, the site was intended as a place of display for herself and her friends to enjoy, but drew much wider attention as its relevance was recognised by the wider community, gaining 1000 likes by the end of its first day and today standing at more than 20 million.

Attracting not just ‘likes’ but also a great deal of commentary and discussion, IFLScience shows the extent to which this format – presenting a curiosity and generating discussion around it – continues to resonate with the public and amateur scientist. The curation of scientific content via Facebook, the digital wonder cabinet, has enabled Andrew to create a career in science communication, and she is regularly invited to speak to scientific conferences around the world. Just as Ole Worm’s curation and discussion of science led to a lasting association of his cabinet of wonders with scientific discovery and learning, so Andrew’s IFLScience page has functioned as a digital wonder cabinet, bringing scientific discoveries and curiosities to new audiences.

Digital Dodos

One of Tradescant’s curiosities was the taxidermy Dodo which can be seen today in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. The Dodo has become synonymous with things that once existed but have become forever lost to us as living participants in this world, and only faint traces, such as a painting or stuffed specimen, remain.

One question that Tradescant’s stuffed Dodo raises in the digital age is when once lively things disappear, will we have any record of their ever having existed? You might have an Facebook page today, but did you also once have a page on MySpace, maybe at its peak in 2008? How long has it been since you visited it? Do you know if it even still exists?

Or going back further, maybe you had a GeoCities page when it was the third most popular site on the world wide web in 1999. When Yahoo shut down GeoCities a decade later, most of the 38 million pages created disappeared from the live web.

Projects like the Internet Archive (link: http://archive.org/web/) and the UK Web Archive (link: http://www.webarchive.org.uk/ukwa/) are an attempt to save and preserve the internet as it changes, evolves and parts of it disappear. Try looking up a page from your past: do you remember when the internet looked like that?

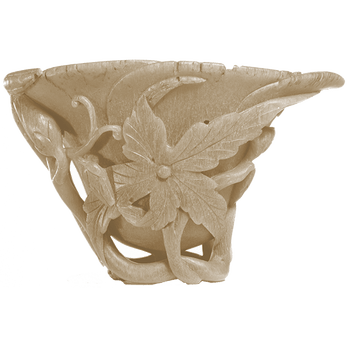

Craft and Making

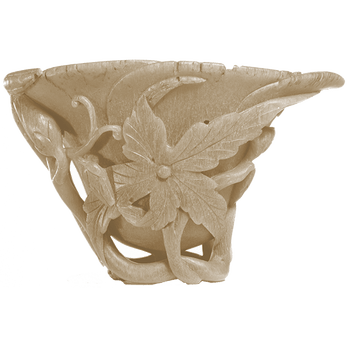

This rhinoceros horn cup from the Tradescant collection is carved in the shape of a five-petalled hibiscus flower. We don’t actually know very much about its creator, or even have much certainty about whether it dates from the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Somebody living in China in the late Ming and early Ch’ing periods likely created it, but we don’t know who or why.

This rhinoceros horn cup from the Tradescant collection is carved in the shape of a five-petalled hibiscus flower. We don’t actually know very much about its creator, or even have much certainty about whether it dates from the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Somebody living in China in the late Ming and early Ch’ing periods likely created it, but we don’t know who or why.

What is certain is that humans have been creating similarly delicately carved objects for a wide variety of reasons for almost as long as they have been human. Why do we make things that are not just purely functional, but liven up our lives with a beauty, colour, and even whimsy?

For instance, there are thousands of photos on Flickr and blogs of bento box lunches such as the one shown here. Their creators have sculpted delicately carved food items that will soon be eaten. The internet, however, gives a new life to these beautiful and quirky objects when they are preserved as a digital photograph and shared for the world to see.

Without a doubt, the internet has opened up new possibilities for creativity and sharing the things we make, whether that involves working with physical materials or creating digital art. However, we know from OII’s national survey of internet use (OxIS) that only a minority of internet users share their creative outputs online. Do you have a creative outlet in your life and have you shared your creativity online? If so, what sort of reaction do you get? If not, have you ever considered doing so?

Fame and Celebrity

This hawking glove from the Tradescant collection likely once belonged to Henry VIII, although the exact provenance isn’t certain. The style of the glove is consistent with others of that time period, and Henry VIII was passionate about hawking. In all probability it is one of the items given by royal warrant to the elder Tradescant in 1635.

Would the glove be as interesting to us were it not for the association with royalty, and in particular very famous royalty such as Henry VIII? Items in historic Wonder Cabinets were frequently said to be associated with famous historical or contemporary figures, but often without much proof of the association.

Twitter is the online home of many contemporary celebrities, and you can follow a famous person with only a click. However, it is just as easy for someone wishing to mislead others by setting up a fake Twitter account. So, you may find yourself following the fake Cheryl Cole instead of the real Justin Bieber when you are looking for insightful commentary on world politics.

More seriously, the possibility of connecting however tenuously to famous people regardless of one’s geographic location or economic circumstances is unprecedented. If you are one of the 10 million people who follow Stephen Fry’s tweets, you are a collector of that connection, and if you are one of the 50 thousand people he follows back and he re-tweets your message, you will have used that connection to gain visibility for your thoughts and ideas by virtue of being able to share a bit of that fame to gain people’s attention.

Cabinets of wonder were essentially performative, as well as contemplative spaces, where the curator could collect and display objects that created a refined sense of culture, as well an indication of wealth and power. The original cabinets often contained curious and beautiful shells, minerals and other geological samples, as well as ethnographic specimens from distant and exotic locations. They also contained many images and statues depicting the classical world. These objects and images collectively displayed the wonders of the world, and the discernment with which the collector had chosen and assembled them.

Cabinets of wonder were essentially performative, as well as contemplative spaces, where the curator could collect and display objects that created a refined sense of culture, as well an indication of wealth and power. The original cabinets often contained curious and beautiful shells, minerals and other geological samples, as well as ethnographic specimens from distant and exotic locations. They also contained many images and statues depicting the classical world. These objects and images collectively displayed the wonders of the world, and the discernment with which the collector had chosen and assembled them.

This rhinoceros horn cup from the Tradescant collection is carved in the shape of a five-petalled hibiscus flower. We don’t actually know very much about its creator, or even have much certainty about whether it dates from the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Somebody living in China in the late Ming and early Ch’ing periods likely created it, but we don’t know who or why.

This rhinoceros horn cup from the Tradescant collection is carved in the shape of a five-petalled hibiscus flower. We don’t actually know very much about its creator, or even have much certainty about whether it dates from the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Somebody living in China in the late Ming and early Ch’ing periods likely created it, but we don’t know who or why.