Dr Julia Slupska

Former DPhil Student

Julia Slupska was a doctoral student at the Centre for Doctoral Training in Cybersecurity and the Oxford Internet Institute. Julia previously graduated from the LSE and the OII.

Julia Slupska, Doctoral Candidate, Oxford Internet Institute (OII) and Scarlet Dawson Duckworth, Cyber Technology Specialist at Darktrace and OII alumna, share their perspectives on the limitations of mainstream approaches to cybersecurity. Together they explain why an alternative feminist cybersecurity method is needed, explored in detail in their new report, ‘re:CONFIGURE Feminist Action Research in Cybersecurity’.

How does cybersecurity make you feel? The field is often imagined as a shadowy realm which is overwhelming, confusing or too obscure to navigate alone. We all manage threats online, yet in popular culture, cybersecurity is practiced by the (usually white and male) teenage hacker in a hoodie, the nerdy yet brilliant inventor, or the socially inept IT guy. These stereotypes are also reflected in the industry and mainstream approaches to cybersecurity. Powerful actors such as companies or the military are the main focus of defence, while ordinary people are seen as the weakest links in security chains, or a “human factor” to be mitigated. Women, particularly women of colour, and queer people are disproportionately targetted by online harassment, stalking, and image-based sexual abuse. Yet such threats are often dismissed as a “privacy concern” outside the scope of real cybersecurity research. When researchers and advocates do address personal security, we too often rely on technical jargon and victim-blaming: i.e. chastising users for choosing weak passwords, clicking on phishing links or sharing nudes.

Security experts determine what counts as a security threat, positioning their worldview as an objective “threat model”. In contrast, feminist standpoint theories stress people’s lived experience as a valid, socially-situated source of knowledge. Although there is no one unified “feminism”, feminist methods often also pay close attention to care, emotionality and participatory collaboration. The Reconfigure project was founded on these tenets. Over the course of ten months, we facilitated community workshops where people could reflect on their digital practices, define their own cybersecurity threats, and take steps to address them in an open and non-judgemental space. These workshops combined digital security tech support with opt-in data collection to pilot a form of “participatory threat modelling”.

¹Thank you to Becky Kazansky for the slogan “security must be feminist”!

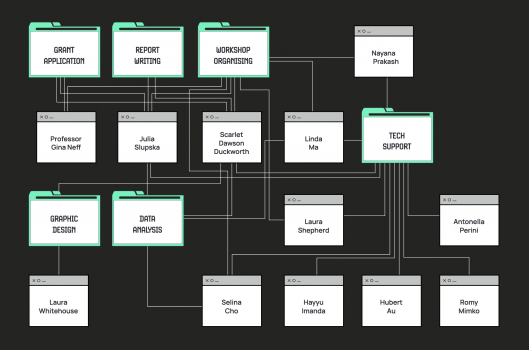

Caption: A network illustrating all the contributions which made this report possible

This approach brings a wider variety of people into the security process known as “threat modelling”, i.e. identifying assets, threats, vulnerabilities & mitigations.

Our workshops were free and run in community spaces (later online as the pandemic hit). We were lucky enough to partner with some wonderful organisations, and we would like to extend a warm thank you to Common Ground Oxford, People & Planet, My Image My Choice, Victims of Image Crime, Oxford Extinction Rebellion and the Edinburgh Anarchist Feminist Bookfair.

We started each workshop by asking people to decide for themselves which parts of their online lives they wished to protect, or to identify what made them feel threatened online. Our volunteers then supported participants in taking action to address those threats, drawing on the amazing DIY Guide to Feminist Cybersecurity and other resources. We concluded with a general discussion reflecting on our experiences of cybersecurity. Those who attended could choose to share their thoughts using an online form, but were also welcome to participate without taking part in the research.

Caption: a Reconfigure workshop at Common Ground Work Space in Oxford

Our participants’ enthusiasm, care and thoughtfulness about their own security, as well as that of their loved ones, stands in stark contrast to the stereotype of lazy, uninterested technology users which is all too common in cybersecurity narratives. That being said, feelings of avoidance, a lack of awareness, and jargony technical language are common barriers to engaging with cybersecurity. Creating community spaces for reflection and action where we can support each other in addressing online threats is a powerful way to overcome these barriers. These actions can be small and personal, like downloading a password manager, or practicing “digital self-care“. However, the burden cannot be borne by individual citizens alone. State and corporate actors must take more responsibility for creating safer online spaces.

This reconfigured cybersecurity is also more sensitive to the intersecting points of privilege and oppression that inevitably shape life online. By respecting these experiences as a valid source of knowledge, we learn about a wider number of threats which affect people who have a different standpoint to the average security expert. For example, one participant described how their online banking account still used their legal deadname, putting them at risk of being outed as a trans person with every financial transaction. Such risks can be life-threatening, yet are easily missed in monolithic, orthodox understandings of digital security.

Going forward, we aim to set up recurring workshops and reach out to communities which are disproportionately targeted by online surveillance and harassment. These workshops would also focus less on individual actions and security tools, and more on developing community and structural solutions. We hope this project seeds change on multiple levels. In the short term, we believe our workshops empowered participants to be more proactive and engage critically with their own digital practices. In the long term, we hope to see a popularisation of these methods and those of like-minded researchers as a path to democratise cybersecurity.