Eve Ahearn

Former MSc Student

Hi Taylor, this is Eve Ahearn and Corinne Cattekwaad here.

We realize you’re quite busy in between ‘never going out of style’ and being named business-woman of the year by a small Dutch newspaper but we also know you have lots of thoughts on the importance of copyright. Not only was your album 1989 the bestseller of 2014, you made headlines worldwide that year by pulling your discography from the music streaming service Spotify. We also know you care about copyright, because we read the op-ed you wrote for Wall Street Journal on the future of the music industry. In it, you describe yourself as an “enthusiastic optimist: one of the few living souls in the music industry who still believes that the music industry is not dying…it’s just coming alive.” There are reasons to be optimistic, but the present situation of copyright in the music industry might not be what you think it is, and this difference might not be such a bad thing for the music industry either.

The MPAA claims that piracy reduces the revenue of music industry, and from your words in the Wall Street Journal it is clear Taylor, that you agree. You write, “Piracy, file sharing and streaming have shrunk the numbers of paid album sales drastically.” However, academic research has not held up the MPAA’s argument. In the Netherlands Joost Poort et al examined the effect of the blocking of the torrenting site Pirate Bay. The blocking of Pirate Bay, put in place by several Dutch ISPs, had little effect on rates of illegal downloading. A recent study by the European Commission showed that online piracy does not hurt music sales and that streaming services actually have a positive effect on the sale of music (EC JRC 2013).

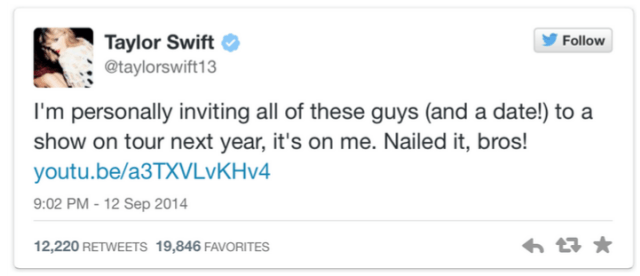

Who does the current copyright regulation benefit then? The current state of copyright cannot be discussed without a mention of Digital Rights Management, or DRM. DRM typically attempts to lock a media purchase to a specific platform. For example, a song that can only be played through iTunes, or an e-book that can only be read on a Kindle. By locking customers into a platform, DRM protects the rights of the platforms over the rights of the musicians. As you know Taylor, from walking out on Spotify, DRM makes it difficult for artists to negotiate as the platforms are so integrated into a listener’s life. Furthermore, DRM prevents fair use of music, for things such as commentary or parody, like the Shake it Off parody video you shared on Twitter. Because the Delta Sigma Theta frat brothers are parodying Shake it Off, their reuse of the song should fall under fair use, but many parody videos have been blocked on YouTube by song-recognition algorithms that consider any use of a song to be a copyright violation regardless of the intent of the video.

The Copyright ‘protection’ measures like DRM show a lack of understanding on the part of the copyright holders and these lock-in platforms of how digital devices and the Internet work. It overlooks the fact that computers and other digital devices function by making regular temporary copies of programs and files, and that making or sharing content is an integral part of the Internet’s functioning.

Although DRM leads to problems for artists, the way to address this problem is not by deciding to withdraw from new technological developments, especially as the ability of individuals to ‘remix content’ (Lessig 2008) on the Internet has become a vital part of today’s music economy. New media provide new ways for artists to generate income, such as advertising dollars from Vevo music video views. Furthermore the ability of individuals to remix content also contributes to expanding the cultural conversation, allowing multiple voices to be heard. And we should not underestimate the extent to which artists have always build upon the work of those that came before them. Without Michael Jackson, without Madonna, no Beyonce. Without Madonna, no Taylor Swift. The creep of copyright law in the United States is best evidenced by the recent jury decision on whether the Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke song “Blurred Lines” infringed on Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give it Up.” The two songs do not share a melody nor any exact sample but rather a tone of a song recorded amidst a party. (You can read a more thorough run-down of the copyright implications of that case by Tim Wu in the New Yorker here.) You told Rolling Stone that your album 1989 was influenced by a slew of 1980s pop stars from Phil Collins to Madonna and Annie Lennox. What kind of pop landscape would we have if musicians couldn’t build off the vibes of their predecessors?

The digital era is not the first wave of changes to the music industry. Live performers were terrified by the threat of radio, then another generation of music industry execs fretted about the introduction of cassette players that could easily record songs off the radio. Taylor, you’re right that digital music piracy doesn’t necessarily equal the death of the music industry. People are still passionate about music. As with radio, the Internet can also lead to new profit streams: someone just needs to figure out the best way to do it. Let’s talk more about this. Eve, at least, will be at your show in Hyde Park in June. See you there.

xoxo,

Eve and Corinne