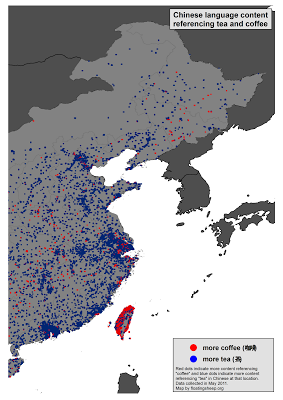

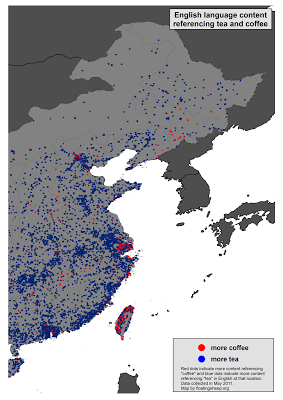

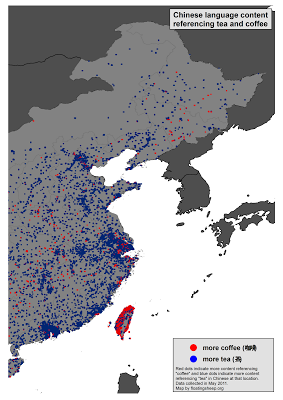

As part of our ongoing research into the online geographies of mind-altering substances, we present in this post an analysis of caffeinated beverages in China and Taiwan. In these first two maps we compare references to tea and coffee in both Chinese and English. You see that mainland China is almost entirely dominated by references to tea in both languages. Taiwan, in contrast, is mirrored by many more references to coffee in both languages. Somewhat surprising is the fact that there are some small pockets of coffee references on the mainland in English (notably Shanghai and a few in Beijing).

Is this an indicator of a move towards more Western types of consumption (i.e. coffee) in Taiwan and Shanghai? Or perhaps it reflects areas of with larger populations of coffee-drinking expatriates? Or — in a completely unwarrented, speculative and highly alarmist vein — it could be a sign of an impending trade war (reminiscent of the Opium Wars) in which Caramel Frappuccinos are used to balance the western (largely American) trade deficit.

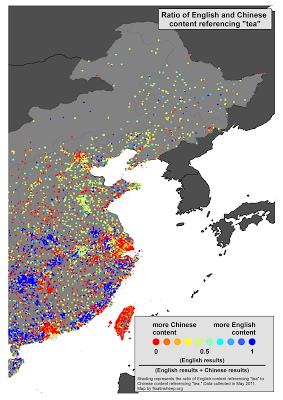

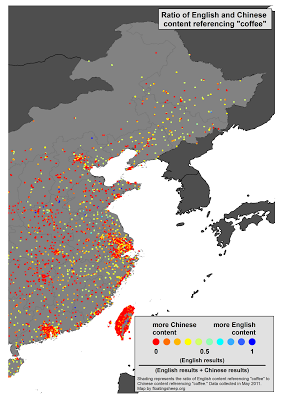

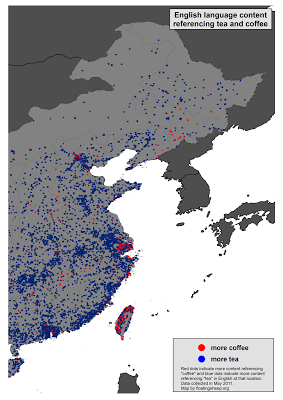

The answers are unclear, but we can explore the data further by comparing the relative visibility of references to “tea” and “coffee” in English and Chinese:

What we see here is that while there is unsurprisingly more Chinese content referencing both tea and coffee in most parts of the region, there are interestingly more references to tea in English in large parts of rural China. Many of these blue blotches of English-language references are actually layered over tea plantations in the south of the country. It is possible though that the English-language references to tea tells us more about Internet content in China than hot green or black beverages. In almost all of the cases in which there is more English-language content, it is because the English word (“tea”) receives only one hit while the Chinese word (“茶”) receives none. So, the explanation for these differences could simply be that Google has just not got around to indexing local content throughout much of rural China.

In any case, next time you hear some use the phrase, “not for all the tea in China” point them to these maps so they have a better sense of what they’re giving up.

Thanks to Han-Teng Liao for the help with this post.