Dr Martin Dittus

Former Data Scientist at the OII

Digital geographer and data scientist. Mass-participation platforms, large-scale data analysis and visualisation, information geographies, social implications of emerging technologies.

You may have seen the news earlier this year that two large darknet marketplaces, Alphabay and Hansa, have been taken down by international law enforcement. Particularly interesting about these takedowns is that they were deliberately structured to seed distrust among market participants: after Alphabay closed many traders migrated to Hansa, not aware that it had already covertly been taken over by the police. As trading continued on this smaller platform, the Dutch police and their peers kept track of account logins, private messages, and incoming orders. Two weeks later they also closed Hansa, and revealed their successful data collection efforts to the public. Many arrests followed. The message to illicit traders: you can try your best to stay anonymous, but eventually we will catch you.

By coincidence, our small research team of Joss Wright, Mark Graham, and me had set out earlier in the year to investigate the economic geography of darknet markets. We had started our data collection a few weeks earlier, and the events took us by surprise: it doesn’t happen every day that a primary information source gets shut down by the police… While we had anticipated that some markets would close during our investigations, it all happened rather quickly. On the other hand, this also gave us a rare opportunity to observe what happens after such a takedown. The actions by law enforcement were deliberately structured to seed distrust in illicit trading platforms. Did this effort succeed? Let’s have a look at the data…

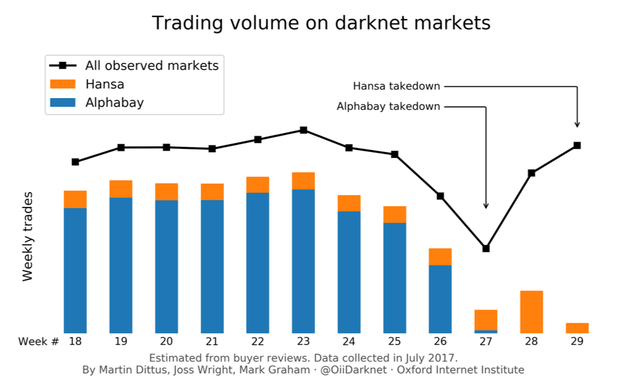

The chart above shows weekly trading volumes on darknet markets for the period from May to July 2017. The black line shows the overall trading volume across all markets we observed at the time. Initially, Alphabay (in blue) represented a significant share of this overall trade, while Hansa (in yellow) was comparably small. When Alphabay was closed in week 27, overall sales dropped: many traders lost their primary market. The following week, Hansa trading volumes more than doubled, until it was closed as well. More important however is the overall trend: while the takedowns lead to a short-term reduction in trade, in the longer term, people simply moved to other markets. (Note that we estimate trading volumes from buyer reviews, which are often posted days or weeks after a sale. The apparent Alphabay decline in weeks 25-27 is likely attributable to this delay in posting feedback: many reviews simply hadn’t been posted yet by the time of the market closure.)

In other words, within less than a month, overall trading volumes were back to previous levels. This matches prior research findings after similar takedown efforts — see below for links to some relevant papers. But does this suggest that the darknet market ecosystem as a whole has a kind of distributed resilience against interventions? This remains to be seen. While the demand for illicit goods appears unchanged, these markets are under increasing pressures. Since the two takedowns, there have been reports of further market closures, long-running distributed denial of service attacks, extortion attempts, and other challenges. As a result, there is renewed uncertainty about the long-term viability of these platforms. We’ll keep monitoring…

Further reading (academic):

Further reading (popular):