11 Apr 2014

by Jonathan Bright and Taha Yasseri.

In the last post we looked at patterns of access to the Wikipedia article on the European Parliament election, 2009 identified an electoral information cycle which consists of a build up period, a peak of information seeking, and a period of decline. In 14 of the 19 language groups we looked at the dimensions of this pattern were very similar: that is, build up periods featured little information seeking until the few days before the election, peaks were short in duration and occurred just after the election, and periods of decline were very rapid.

In this post we want to focus on the 5 languages which didn’t fit into this trend, which were Estonian, Italian, Maltese, Norwegian and Dutch. Conveniently, each one of these languages overlaps almost perfectly with a single country, meaning that we can engage in some speculation about how the characteristics of different national systems affect patterns of electoral information seeking.

Both Malta and Norway featured very low absolute numbers of views to the web page in question, which presumably relates to the very low absolute population of Maltese speakers, the fact that Norwegian citizens don’t vote in EU Parliamentary elections (Norway does adopt lots of EU legislation through EFTA, so a very politically motivated Norwegian might still get interested to an extent), and of course the fact that English is widely spoken in both countries, meaning that they would have access to the English version of WIkipedia.

Of more interest to us are the patterns emerging from the Estonian, Dutch and Italian cases. Each one is distinct so we’ll look at each of them in turn.

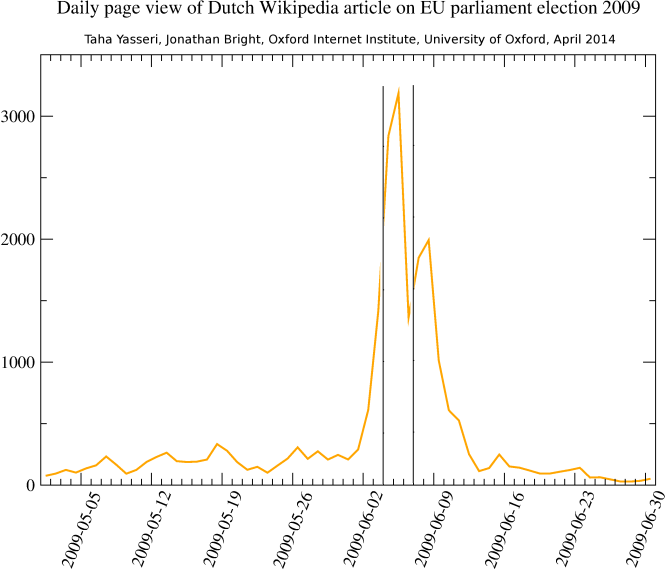

Above is the situation in the Netherlands, which is unusual in that it presents two peaks of activity. The first falls the day after the Dutch portion of the EU elections took place (on the 4th of June), the second on the day after the last day of the election period defined by the EU as a whole. Both events are likely to provoke media coverage and hence drive searching, consistent with our media effects thesis expounded in the last post. However it is also worth noting that the European Commission prohibits distribution of country specific election results until all results are in from all countries in Europe. This means that Dutch voters would have had a several day wait to find out the results of the election they participated in. It could be in other words that instead of being generated by a media effect, this searching is generated by people who want to know the election result but haven’t been able to find it reported in the media.

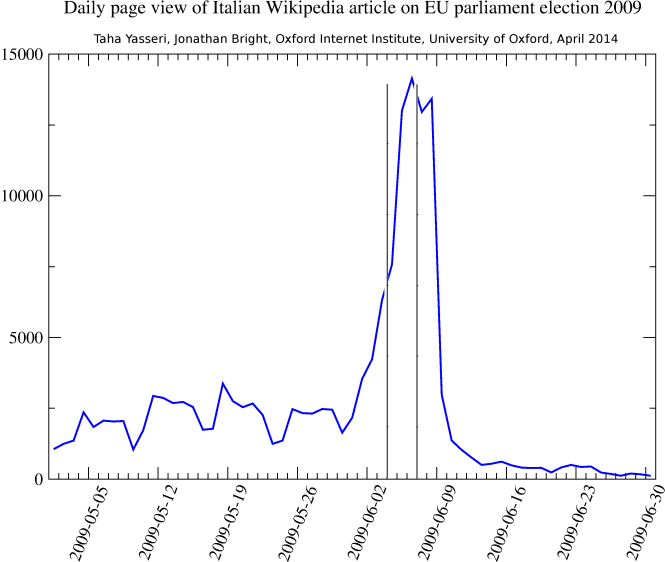

Above is the situation in Italy. The country is unusual in that the build up period features a relatively large amount of activity (with a clearly visible weekly cyclical pattern), and also in that the peak of information seeking is sustained over several days. A couple of thoughts emerge. Firstly, Italy is known for having an electoral silence law which prevents opinion polling in the 15 days before the election, and any type of campaigning in the day or so before it. It could be that this relatively high build up period is a result of a dearth of information in the media about the elections.

Secondly, the Italian part of the European Parliament elections took place over two days (Saturday afternoon and Sunday). This may explain the longer peak, as people who participated on Saturday might search for the results on Sunday, whilst others might look on Monday.

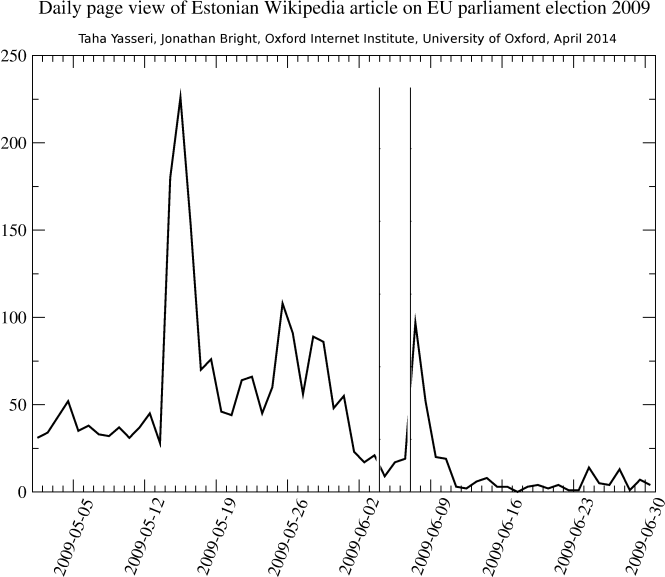

Finally, we present the view from Estonia. The absolute numbers in this country are very small meaning that we shouldn’t read too much into it. However the pattern is highly unusual, with a peak falling well in advance of the election, meaning that we wanted to say something about it.

The Estonian part of the 2009 European Parliament elections was unusual for two reasons. Firstly, it featured a dramatic 17 point rise in turnout. Secondly, against a backdrop of frustration with the major parties, two independent candidates gained a significant proportion of the votes. How does this relate to an early peak? Honestly it’s not quite clear: perhaps more would need to be known about the specifics of the campaign. Nevertheless it feels relevant that this unusual pattern of information seeking coincided with an unusual electoral result.

Conclusions: Of course this is all speculation at the moment, however what emerges from this is an alternative thesis to the “media effect” discussed in the last post. Rather than seeking electoral information in response to reporting in the news media, voters may seek it because of a lack of such reporting (either because of an electoral silence law or a delay in the publication of the results). Such effects may be sharpened in an environment with new or unusual candidates. This is important for our overall question because it suggests that those who are seeking the information are likely to be those who participated in the election.

Next steps: see if any of these ideas can find support in the results from other countries. Did other countries which voted on the 4th of June have a twin peak style pattern? Are there any other electoral silence laws? What about victories for independent candidates?